How we build Beampipe

Originally published here.

I wanted to kick this blog off with a discussion of some of the technical decisions we made while building beampipe. However, I guess I can’t really get away without talking at all about what the product is so here goes…

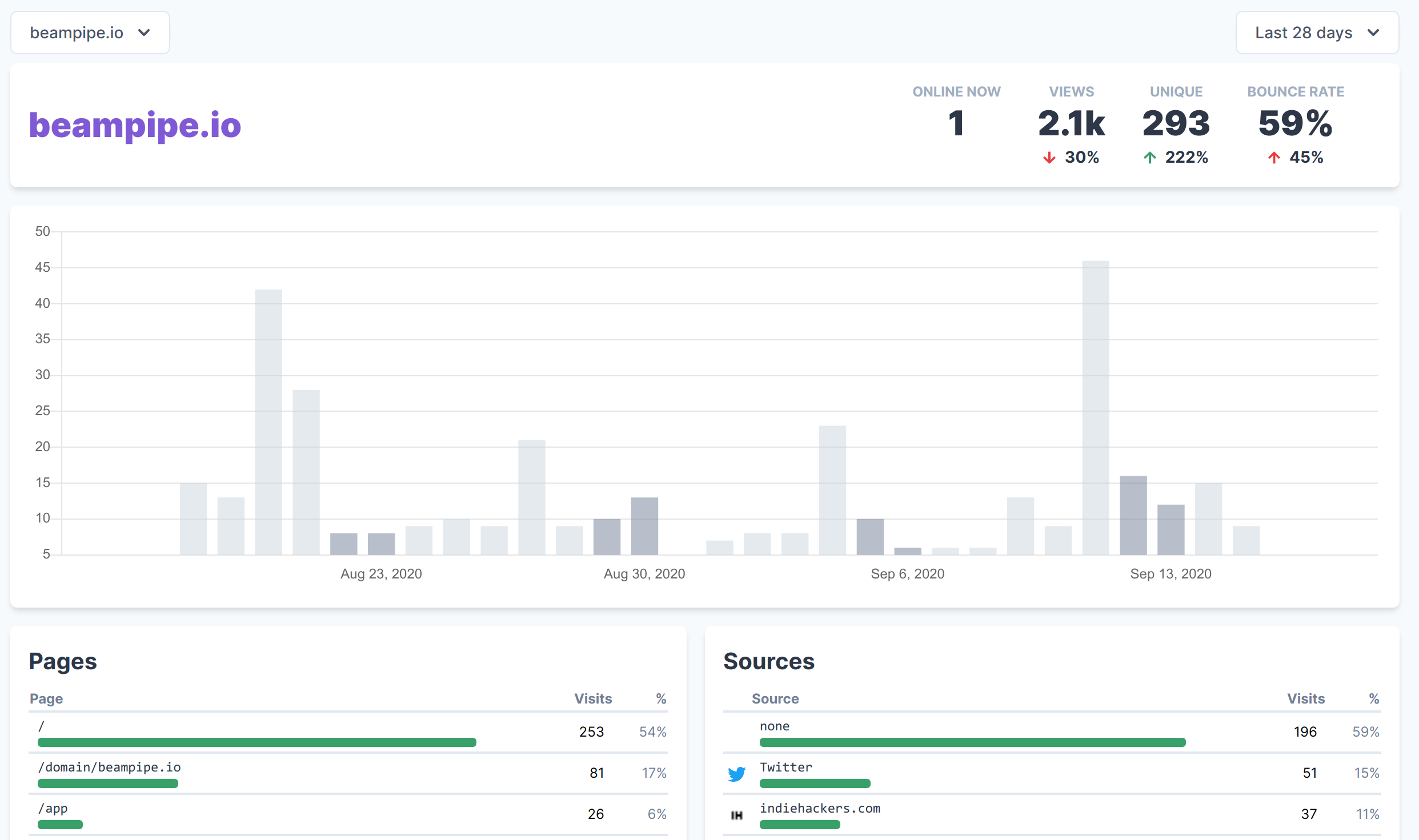

Beampipe is a simple, privacy-focussed web analytics tool. It’s somewhat similar in concept to Fathom and Plausible but with some slightly different goals, particularly with regards to our future roadmap. Put simply, and most fundamentally, we think web analytics tools should be easy and fun to use. Secondly, we think that where possible, these tools should respect user’s privacy. We take the same cookieless approach as the two aforementioned tools and explicitly not that of Google Analytics. Thirdly and hopefully distinctively, we think web analytics tools should be powerful. They should give you useful, actionable insights. We feel that there is no tool on the market ticking all three of these boxes and that we can build it!

Ok so now that I’ve kept our marketing department happy, how are we building it? I’m going to start out by describing how a web analytics service works.

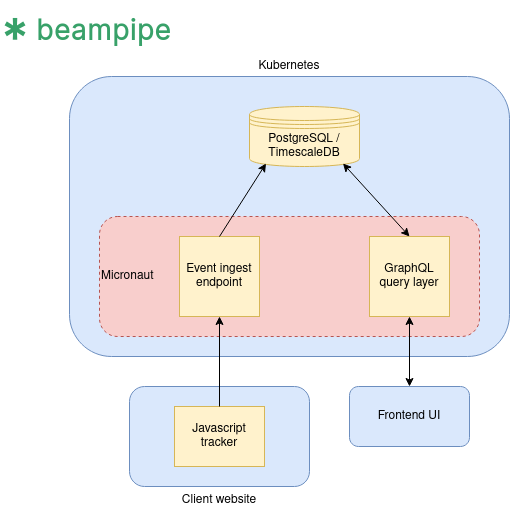

All of the products I name-dropped in the preamble function in basically the same way. You drop a little (or not-so-little in the case of Google Analytics) chunk of Javascript onto your page. That Javascript will then make a connection to a backend service and phone home with a little blob of data describing (to various levels of detail) who the user is and what they’re doing on your site. There are some variations here: for instance that you can forego Javascript in favour of an invisible image. But that’s pretty muchthe size of it.

So the first piece to any web analytics service is to build this tracking script and a suitable backend to process and store the data that it spits out. So what did we choose here?

Kotlin + Micronaut

I’m a big fan of Kotlin, a relatively new programming language from the JetBrains. Kotlin is built upon the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), inheriting a huge base of libraries and frameworks as well as an extremely performant runtime. On top of this, and much more importantly from my perspective, it is extremely fun and productive to write code in. It mixes in just enough functional programming magic to make you feel clever and powerful without quite the learning curve, cognitive burden and multiple competing styles that comes with languages like Haskell (or to a lesser degree, Scala).

On top of these strengths, Kotlin also has some very nice support for asynchronous programming using coroutines, which can be quite an advantage from two perspectives:

- Performance. I/O heavy code can share operating system threads. This helps us keep our costs down.

- Reasoning about concurrency. We have several features within the application which call out to external APIs and may perform a chain of operations on the results, handling errors appropriately. Coroutines, in my opinion at least, give a nice readable way of structuring this logic.

On top of Kotlin, I had to pick a web framework. For this I chose Micronaut which is a fairly full-featured JVM-based web framework with some specific support for Kotlin. Whilst I’ve previously preferred less full-featured frameworks, I’ve actually found that, once through the learning curve, Micronaut gives you a lot of useful stuff out of the box without forcing you to use it (e.g. security/authentication, database connection pools, GraphQL).

Database

So here we come to perhaps the most important choice. Web analytics tools have some fairly specific needs from a database point of view and ones I shan’t pretend to be an expert in. Write rates are high (at least once people are using the tool). So we need something that can support a fairly high sustained write rate (equivalent to the peak simultaneous traffic for all of the sites using the service). Secondly, we are dealing with timeseries data — something for which certain databases have specific support. Query patterns against the data are often going to be so-called OLAP queries — i.e. aggregations over various axes in the recorded data.

There are a lot of potentially good database choices here: influxdb, clickhouse, bigquery, redshift etc. However, two concerns led our decision: low overall ops overhead and low cost (since we want to be able to offer a free tier for the service). For this reason, we chose TimescaleDB which is a plugin on top of the excellent PostgreSQL database. This means we only have to live with a single database (including our non-timeseries data) and let’s us get started quickly and at low cost. In future, we may well switch out for something else, but this has served us well so far.

APIs

Having strong API support is part of the longer term vision for the product. We want our customers to be able to integrate deeply with their analytics data. We also want to build a fantastic frontend experience and do it quickly (the first version of the product was launched within a week).

Thus we chose GraphQL. Why? Web analytics data is not well represented by a graph and thus doesn’t really benefit from GraphQL’s namesake feature. On the other hand, we’ve found it very useful for building rich APIs with more sophisticated querying capabilities. It is also strongly typed, meaning that users of the API can have some confidence in the shape of the data structures returned. Lastly, alongside frontend libraries like apollo-client or urql we have a very opinionated, simple and powerful way to hook our web interface up to backend queries. This makes development easy and code readable.

Build/DevOps

So first an admission, despite the pronouns employed in this blog post, Beampipe is a single engineer at the moment — namely me! As a full stack engineer with a lot of ground to cover, automation is key. On the other hand, I have to pick my battles. Continuous Integration (CI) tooling is essential. I simply don’t have time to be manually testing, building and uploading things every time I make a change, at least not if we want to maintain velocity on the product. But I also don’t have time for the kind of build and deployment pipeline you might find on bigger engineering teams.

For this reason, I build the backend code as a Docker image using GitHub Actions. The build itself is coordinated with Gradle and makes use of Google’s handy jib plugin which produces small, cacheable docker images.

Deployment is another area where there were trade-offs to be made. I’d love to use something like Heroku and really not have to worry about deploying the application. On the other hand, these tend to be quite cost prohibitive and not necessarily a good fit for how I wanted to build the app. For that reason, I picked Kubernetes on Scaleway’s hosted Kapsule service. I’ve used this for a few projects now and it’s been excellent.

Currently the backend is deployed as a monolith but it should be fairly easy to split things up should we need to scale component individually (e.g. separating the data ingest service from the query layer).

So that pretty much wraps it up on the backend pieces of the app. In the next article we’ll discuss the frontend in a similar manner. Hit me up with questions or feedback on hello@beampipe.io Cheers!